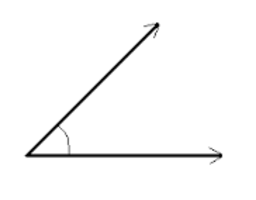

Coverage Angle Test

By: Victoria Osaji, Manufacturing and Development Engineer

Table of Contents

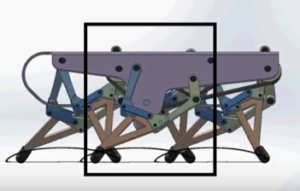

Design Analysis:

Introduction:

This was one of the four tests we conducted to demonstrate the mechanical capabilities of our robot dinosaur. In this test we are looking to determine the radius our robot head can cover essentially measuring what areas our robot can see as it moves its head around. This way we know the limitations on the robot head so as not to damage any of the linkages or the internal components which are tied together

Process:

Parts needed:

- Flat surface area

- Protractor to measure out the radius angle

- Ruler

In order to measure the coverage angle the steps and measures we took are show below:

1. Set your robot head to the middle of your robot and mark that distance

2. Move your robot head as far to the left as possible without moving the body. Mark that spot.

3. Move your robot head as far right as possible without moving the body. Mark that spot.

4. With a protractor measure the angle covered from the left to the right.

5. This is the range that your robot can visually cover.

We repeat this exercise a few more times to validate the range we are getting on the robot

Results:

What we noticed is our robot moved 160 degrees to the right when turned and in the reverse direction 20 degrees to the left when turned. On average the consistent rotational angle we saw was 140 degrees. We repeated the exercise and had several numbers in ranges of 138degrees all the way to 142 degrees (we had about 8 different tests conducted). Therefore our 140 degree was an average of the all the samples we attained.

Conclusion:

All in all, there are several important factors for why we want to know what our coverage angle. We do not want damage linkages or any parts of our robots by awkwardly turning it in directions it is not able to go. Therefore understanding what our limitations are with regards to knowing what our coverage angle is will help to protect our robot.